Board Games, Meet Video Games

Worker placement. Deck building. Drafting. These terms are familiar to fans of modern board games like Agricola and 7 Wonders, but not so much to video gamers. Board games are experiencing a golden age of innovation, with a constant flood of brilliant games that often invent entirely new genres. Video games are undergoing a nostalgic renaissance of multiplayer games, recalling childhoods spent playing Mario Kart and GoldenEye on the couch with friends. We wanted to harness these two movements and create a little revolution of our own.

In Those Days, In Those Far-Off Days

The game that brought it all together is older than we are.

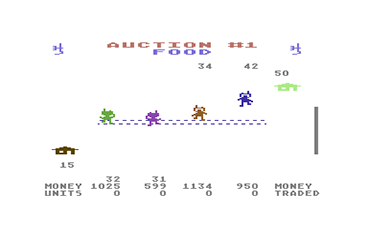

Ozark Softscape’s M.U.L.E. was the masterpiece of the late genius Dani Bunten. It came out in 1983. Everyone who played it fell in love with it, but it didn’t reach a mass audience.

M.U.L.E. combined exciting real-time interactions with an intense economic simulation based on supply and demand. It was one of the first good multiplayer games for home consoles. When we played a modern remake, we were hooked. Here was a game that combined strategy with action in a meaningful way. It was clever and charming and tons of fun. And no one had made anything like it for the past three decades.

Crafting the World

We wanted the game to be about building up a city from nothing. It made sense to set the game in Sumer, the cradle of civilization. We also liked that Sumer had been underexplored as a historical setting for games.

Our first paper prototype was fun, but translated terribly into digital. We discovered that board games and video games have different expectations. A great board game might make an awful video game.

For one thing, players don’t want to listen patiently to video game rules - they want to start playing and figure it out themselves. For another, video games have to feel good. Every interaction needs to be satisfying, even just moving your character around. Finally, some mechanics simply don’t translate well, or at least need to be reinterpreted. We had an auction, for example, but it wasn't fun at all.

Armed with this knowledge, our next iteration took on roughly the shape of the game today. Inspired by ancient murals, we made the game a platformer and set it on a ziggurat. You jumped around, gathered resources, and put them in rituals to gain points.

That was it. All our other mechanics were gone - it was a worker placement platformer.

Creating Order

It was the right direction, but the game was still bad. Everything was jumbled together. Your strategic decisions were overwhelmed by the sheer necessity of constant action. We took two major steps to rectify this.

First, we divided up the game into days. Each day, players could assign their workers to perform one action, like a round in a board game. They could also wait as long as they wanted before waking up to start the day. This allowed players to form a plan for what they wanted to do that day, so they could think strategically instead of just rushing around. But because the game was still action-based during the day, quick thinking and adaptability remained important.

Second, we brought back the auction, adapting the mechanic from M.U.L.E.'s land grants. Players bid a special resource, silver (later goats), which was not used to gain points in rituals.

Suddenly, we had a flexible economy. We could balance things with goat costs. Players could be more creative with their strategies, depending on how they balanced goats versus rituals. In a word, the game could breathe.

The Future

After those changes, we felt like we had something good. It’s been a long process of iteration, especially on the visual side, and we’re still trying to improve it to be the best it can be.

We love Sumer, and we’re excited to get it into your hands. If it's successful, we hope to design more games like it. We also hope to inspire others, just like M.U.L.E. inspired us, to combine board game design with video game technology and explore this promising new genre.

Here’s to Dani Bunten, and here’s to the future.